Knowledge management: Key findings and lessons Marcelo Hoffmann. 1.* - unedited transcript - Okay, thank you, Doug. Okay. So what I will do today is give you a very, very short run-down of knowledge management in the business environment. It will be a very short-twenty minute, or so-presentation. And, take it with a grain of salt--it's meant to be for business because those are our clients. But the meta-lesson from this, if you will take is, is how does this relate to bootstrapping? How does this relate to the government, or NGO's, and so on? We'll have Peter Yim speak afterwards about an NGO and what they do, which in a sense are a type of knowledge management. But my bias will be directly related only to companies because that's the environment where I work. Okay, I have to move this to get-sorry, presentation on the left there? Okay, thank you. So, the concept is nothing new. It's been around for a long time. Different

authors have taken different perspectives on this.

Doug has presented his views. Peter Drucker has written extensively

about knowledge workers. But what is new now is the Internet. It is the

networks; it is the greater computing power and the like.

We can say that the status is pretty much equivalent to the quality movements of 20-30 years ago when you talk about knowledge management in the corporate settings. Everybody speaks of knowledge management as if it were something consistent, unique, individualizable, et cetera; it is not. And I will give some descriptions of what different folks mean by knowledge management and then talk about some cases, some suggestions for implementation, and then what we see in the future. And then, perhaps if you will keep in your mind-how does this relate to Doug's ideas, theories, strategies, and the like. One thing I would like to emphasize-that this knowledge management stuff is not a fad. It's definitely something that will remain for a while, but it will evolve. The popularity has been only in the last five years. It probably might

change in terms of methodology, syntax, semantics, and the like, but it's

not going to go away as some of the other business consulting fad have

come and gone. Perhaps, something to keep in mind, also, is what methodologies

are applicable to be transferred from the knowledge management to bootstrapping?

I believe some will, some will not; but perhaps it's something we should

look at collectively. For lack of a definition, there are many descriptions,

but one thing that is very consistent is something about value-either creating

value, or re-using value, or conversion into or out of value, reuse of

knowledge and the like.

It's a result of many evolutionary processes and trends. But, definitely,

it's mostly about management. When you really get down to it, if you cannot

manage a corporation, you're not going to be able to do knowledge management

particularly well. And, I'll get into that in greater detail later on.

The practices vary. And, these I would to emphasize. Different writers, different authors and consultants speak as if knowledge management were any one of these four components--and sometimes a mix, combination, hybrids, and the like-but all these are included by some anyway. Valuing knowledge has been around for a while, getting increasing importance in terms of recognition and evaluation. Evaluation is very problematic. There are some attempts to go beyond accounting, but it is a matter of judgment. There are no ways to measure and value knowledge in a unique, repeatable way. But there's some ways in which you can compare greater or lesser value. Exploiting intellectual property--that's something that's very much in vogue--particularly by large companies that have been able to reduce the cost of maintaining intellectual property, selling what they have that they're not using. Companies like Dow and Motorola--there are a number of cases where they have used this very effectively both to reduce their cost, and to increase their profitability. Managing knowledge workers-that's been around forever, perhaps since the middle ages. But obviously it's getting more and more important now. And I will emphasize this later on in my presentation--that if there is a meta-message behind this knowledge management, the fad or movement, is that what is being used rather effectively is what's considered explicit knowledge-stuff that falls into databases, knowledge bases, manuals, you know, all the stuff that's obviously very valuable, and useful, and repeatable, and reusable, and so on. What isn't well used, or not as well used, is what's tacit, implicit in people's heads, that sort of thing. We haven't quite learned how to reuse what's in people's heads. But I'll give some suggestions as to technologies that might help reduce the problem of reusing implicit knowledge. The last one is the one that perhaps has the most potential, the greatest value, and arguably, the most difficult to capture. This whole issue of capturing-I will read it directly-sharing/distribution

of work-based learning from the day-today work of knowledge workers. And

this implies from within the firm, outside, competitors, suppliers, allies,

and the like. This is very problematic, and for this you would need to

have something like what Doug calls a Dynamic Knowledge Repository. What

we have seen in the companies we have studied is that this is not done

particularly well. It's done very ad-hoc. Some companies will bet on others,

but perhaps by chance, or by cultural reason, there is no great methodology

that can be transferred. And the practices of the four components that

you see above here do overlap, and at times, keep expanding. Now when looking

at the approaches, the formal approaches used by companies who are very

heavily involved with knowledge management evolve. The first movement,

if you would, of keeping track of repositories has been pretty much done

by most large companies. It's fairly straightforward; it's not that difficult

to do.

And you see all the different kinds of collections of knowledge, or

information, or data, if you would. But the latter component, which we

think is very important, is relatively new-the whole thing about search

engines, data-mining, visualization-making stuff available more easily,

making stuff available when people need it, ideally as they need it. That's

a little bit of a stretch as of now, but perhaps in time. Technology solutions

are coming. The second set of activities; the second set of approaches

is this whole arena of networks. And that's for the purpose of creating,

holding, transferring tacit, or implicit, knowledge. This is much more

problematic. It's much more about managing people, deciding organizations,

evolving organizations and the people who are within them.

Different companies use different approaches. The classic ways are connecting people, teams, and ad-hoc get-togethers. Some of the companies locally you can see they design their offices and their buildings to increase the likelihood that people will meet with others. Several folks here who have worked for Sun will smile when I mention that at the new Sun facility in Menlo Park there are like mini-cafeterias every so often as a way to have folks gathers there, exchange information, knowledge. And, surprise, surprise-there are whiteboards right across there. Well, it is to get this exchange, which cannot be done in other, more formal ways. And, the last point about communities of learning and practice is something that has been going on now for a while, but increasingly there is more attention to this. And, I think that as the technology to connect on the networks, which has become increasingly more powerful, this will become even more popular. However, face-to-face will not go away any time soon. If there's a question about this, perhaps there might be competition with very high definition screens, and so on--if you can get the dynamics that are better than being there. But I'm not sure that, that will be the case-not yet, not for a while anyway.

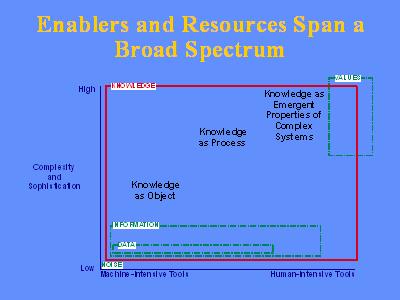

If we look at the enablers and resources that are used for knowledge

management-you can go from the left side, going from noise, data, information.

I spoke about knowledge as object, then going on from knowledge as process.

The higher, right-hand corner will be knowledge as emergent properties.

And this is really tricky to go to. That's something that I believe is

still a research question. Perhaps by using bootstrap in evolving organizations

beyond the current state, this will work out. But there is no methodology

approach that I know of for all the companies I've interviewed, and visited

with, and spoken to. But, in a sense, there is this transition from the

low-end stuff to the higher-end, increasingly more tacit, and more complex,

and much more difficult to transfer.

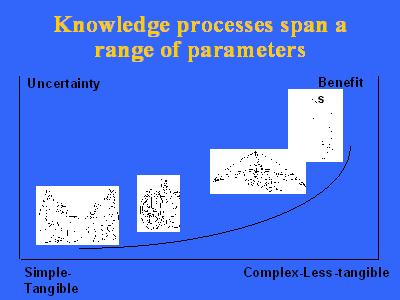

The emphases, by various companies, vary dramatically. If you look here, from the left side, the more mechanistic approaches to the organic. If there's one message that we can convey it's that, in general, most modern companies are going from the left side to the right side, but not all evenly and not evenly down this list of characteristics. One company might be very interested in short-term tactical ideas, but very involved with creativity and innovation, and so on. So, you would see somewhat of a zigzag of organizations if you were to take some sort of measurement across a large number. But, in general, we have seen a transition from the left side to the right side, towards more biological approaches-and also larger-scale, and more chaotic, perhaps going along with, the Santa Fe Institute talks about that, chaos and chaos theory. Another way of looking at this knowledge management and the processes underneath is that they tend to go from the simple/tangible on to the less tangible, but potentially the greater the benefit.

And, when I've given these presentations in different companies and different companies, what tends to come back from the dialog is most companies are at the left-hand corner, bottom left-hand corner. Trying to avoid repeating the invention of the wheel. And they keep doing that, over time, more efficiently. Some are going to the concept of how do they make a better wheel-but not that many, and not often on purpose. If this were drawn to scale, there would be a major chasm between that and the fellow on the hand-glider, because that's changing paradigms. That's very difficult-going from there to thinking about thinking. The meta-approaches that Doug proposes, I have yet to see any organization, any other speaker, besides Doug and the group that's promoting and trying to bring this bootstrapping to happen, suggesting this. So, if there were a chart describing where the companies are that we

have observed, it would be largely at the bottom left, with a few going

up, and the, nobody at the top, right-hand side. And, there might be some

hypotheses about countries, and size of organization, and so on. Going

back to, say, some visits in Japan some time back-Japanese companies, for

example, are very good at not re-inventing the wheel. They transfer that

kind of knowledge relatively well. They have a very hard time with creativity

and innovation, and so on. Different cultures will work differently-better

for some things, less well for others. Organizational models are something

very important to look at for considering knowledge management.

The three kinds of organizations, for lack of a better taxonomy that

we have seen-command-and-control, exchange economy, and gift society. What's

very common is that many speakers present the idea for gift society as

if that were the one that they would get to first. I have yet to see that

happen-if anything, you can get into exchange economy where there's a trade

off: I will give you something if you will give me something in return

that's equally valuable or better. And one of the suggestions we make is

to go for that, to go for the exchange economy. Don't assume that you will

generate a gift society or a gift group just by itself. You have to develop

the trust-go from command-and-control to exchange economy and then to a

gift society. And, in fact, most organizations will probably oscillate

between an exchange economy environment and a gift society environment.

You know, depending if the trust goes up and down. But, it's still better

than working in command-and-control where folks will only contribute what

they have to contribute, and no more. So, this is something to consider

if one were to analyze what is the situation in a particular company and

we suggest to also consider how to ferment the evolution from an exchange

economy to a gift society. What we have found among the cases that we have

analyzed in greater detail is that they're extremely contextual to be successful.

There's no generic approach that will work in different companies.

There are two cases that I have found that are classics: Chaparral Steel,

a small mini-mill, some couple thousand people, and Boeing, the triple

seven-I just couldn't think of Boeing as a company because it's just too

large. But if you can compare Chaparral Steel, they work essentially as

if they were a company working in the Middle Ages with apprenticeships.

And they have their R&B on the production floor, so newer folks learn

from people who have been there longer and who have done steel-making longer,

and so on-very tacit knowledge. Very little use of computers. Once they

sell the steel, it's gone; they don't have to guarantee it anymore. If

you contrast that to Boeing where they have to keep track of everything

they've done for years and years, maybe for 40 or 50 years after the airplane

will fly, it's a very different environment. It's a different approach-and

for good reasons. So if I were to take another metaphor-it's sort of right-brain/left-brain,

but the whole concept here is to be specific. What kind of organization

do you have? What do you want to get out of it? And then, what do you decide

for it? Perhaps, what sort of folks do you hire, train, support, that sort

of thing? One of the suggestions we have found is very useful is, go for

the early benefits. There's nothing better, to build up the bandwagon effect,

than being successful early on. And what we have found within that is the

idea of going after improved knowledge repositories.

It's much easier to prove the benefit of these than to prove the benefit

of a network that might take six months, a year, two years to come up with

something interesting and exciting. Also, going for effectiveness and efficiency,

and even though these may be lower-level gains, they're still useful to

create the environment that, in a sense, will take you to a higher-level.

But one thing to keep in mind-you cannot predict what will happen in the

longer run. Literally, users build the road as they travel it; and it's

a co-discovery between the developers, the designers, participants, and

the like. It's an interesting travel with all kinds of detours. Some of

the risks that we have found in organizations that try to do this fast

is shifts in power, the changes in politics and relationships and so on,

were very problematic. And, often times, the senior manager was not aware

of what the effects would be until after the fact, until it was a major

crash.

And, the problem of implementing this things is also difficult enough

that we suggest: start small, evolve, grow, see what works in your organization,

and then, as long as there are successes, things will evolve nicely. Otherwise,

if you try to do something big, there will be major problems in allocating

costs because those who pay are not necessarily those who benefit. Then,

there will be a major fight for who pays, who gains, where, when. In addition,

these things spread over time, which is very problematic because there

is still-as I mentioned before--not very good ways to measure what the

value of improved knowledge management will be over time. We have found

that there are at least two kinds of resources that are absolutely crucial.

The organizational part, in Doug's terminology, would be the human systems,

the agreements, the excitement, and he commotion of the right kinds of

activities, of behaviors, that sort of thing. We would add mentoring, training,

support to the point of being pedantic.

Definitely leadership from senior executives is very important.

Besides that infrastructure, I will go back to what I mentioned earlier:

even the architecture of the buildings where collaborators work is important-for

folks to meet in an environment that's conducive for them to do what they

want to do, better. Obviously, computers, networks, all that, they are

nice, nothing new there but important to have ongoing mentoring, training,

and support. We have had cases of that, even at SRI, where as Microsoft

keeps changing the software, we need support where we didn't think we would

need support. So, I've had several cases of that myself.

Several things that we see as enablers now that also I mentioned earlier-about

the networks, the tools, the internet-a lot of value will be gained from

the transition from HTML to XML, perhaps KQML, Java, others. I think we'll

have some speakers later--next week and the following week-getting into

this in much greater detail. So, I will not dwell onto this one. Search

technology is going to be very important because soon there will be the

ability to capture, as Jim Spohrer said last week. You know, if you can

have a very small form factor hard drive that can store all the audio for

your whole life, well that's nice, but then how do you find anything. So,

if we have better search techniques and approaches, particularly things

from artificial intelligence-speech recognition, natural language, knowledge

bases, and so on-in a somewhat automated fashion. That'll be quite nice

and useful. These things are here now; they can be used better, but they're

there. Okay, one thing that's coming up, that's not quite there yet, the

idea of cross-referencing multi-media-actually SRI has some efforts on

this where you can cross-correlate different media streams from video,

sound, documents, and so on. And, if you can do what amounts to a multi-media

search, there's a great potential there-both for good and for spying, and

for privacy violations, and for security problems. But still, it's something

worth looking at because it's got very good potential. This whole idea

of automating some of the activities that people do now also has huge potential,

although it will never, or not for a long time, become completely automated.

I don't think people will be pulled out of the loop; but, perhaps the lower-level

activities, thee lower-level tasks, can be automated. I believe Doug goes

along with that in terms of co-evolution and so on. The suggestions that

we have made that seem to be consistent with most of the success cases

that we've seen follow here.

The idea is to start looking at what are the needs. Take a very gook

look at the human organizational elements, factors, environment, culture,

all that. Then start the design process with the knowledge architecture.

What should be the ideal combination of things so that users would get

benefits fairly early on? Only then think of the technology infrastructure,

and then stop. Start doing this in modular fashion: test, improve and repeat

the steps. This is a highly intricate process. I have yet to see any successful

company deploy a formal, large knowledge management system in one fell

swoop. It just doesn't happen; it's too complicated.

Some of the possibilities ahead include: the processes in a much more global fashion--large scale implementations, what Doug talks about, you know, meta-meta levels--large organizations collaborating in a closely coupled fashion, maybe across countries or large enterprises. Another great opportunity is the one to enhance individual and group creativity. That's something we don't have much of a handle yet, but perhaps by reducing the lower-level functions then perhaps folks will have the time and ability to do the higher-level activities. And then, this whole notion of this seamless web of resources combining them in a fashion that is useful at the time that has needed, in the best way. That is a little bit of a pie in the sky for now, but perhaps not in a few years. It is something that we will have to evolve into. And, I want to finish with some comments on a slide presented by Jim Spohrer last week about learning that although when it comes to knowledge management it has taken, to some extent, the first three of these components, performance support, practice skills, habits, and training. It has yet to, within the corporate setting, look at education, research, the finding of new answers and the finding of new questions. There's still a lot of opportunity there, but I'm not sure that we quite have it yet. And, with that, I finish my presentation and cede the floor back to Doug. Thank you.

---

Above space serves to put hyperlinked

targets at the top of the window

|

Fig. 1

Fig. 1 Fig. 2

Fig. 2